Agle, a member of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, moved to Brigham Young University in 2009. He lamented losing his best guest speaker, but O’Rourke agreed to fly to Utah to continue the relationship.

He chuckled when asked how O’Rourke was received on campus.

“The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is different from most religious denominations in how it chooses its leaders,” Agle began. “Our leaders don’t come up through a professional ministry. They are chosen from different professions. I remember when Bill would come to speak, he so impressed the students at BYU that I would often have them come to me and say, ‘He’ll be a general authority of the church some day.’ I would laugh and say, ‘He’d have to become a member first.’ Students couldn’t believe he wasn’t. I absolutely love that our students get to have this interaction with him to see that there is incredible good in other religious traditions.”

Many of the lessons that O’Rourke shared at Pitt, BYU and more than 20 college campuses, including six Jesuit institutions in the last year, revolve around his experience as president of Alcoa-Russia.

His decision to accept that role in 2004 came in a time of uncertainty. He received the job offer one year after his wife, Carol, died of cancer. After consulting with his children, Ryan and Heather, he decided it was the right time in his life for the challenge.

“Imagine that plane ride, the first trip into Russia,” he says, noting that even the CEO was surprised by his choice. “I know two Russian words – da and nyet. I’m heading into a culture I don’t know, a language I don’t know, a place I don’t know. There was fear there. So much unknown. It turned out alright.”

The decision sums up one of O’Rourke’s philosophies in life: when you come to a fork in the road, take it.

“You jump in the deep end,” he says. “Imagine when you first learned to swim. There was fear, but, boy, a lot of joy comes from it. It was a chance to make an impact and make things a little bit better in the process.”

In a deep-seated culture of corruption, O’Rourke stood out by example. He focused on safety at two manufacturing plants that averaged five industrial deaths per year for fifty years. He shunned a lavish penthouse office and moved with his leadership team into open, accessible cubicles. He refused to pay off the local authorities who pulled his car over to demand bribes. He called out blatant extortion in his factories.

His actions continued to cultivate an enduring reputation for ethical leadership. He explains the approach succinctly: “Integrity is the most important attribute of a true leader.”

Dave Lassman, a professor at Carnegie Mellon University, met O’Rourke in 2012 on the board of Sustainable Pittsburgh. Like Agle at Pitt and BYU, Lassman teaches leadership and business ethics. He jumped at the opportunity to have O’Rourke in his classroom.

“Bill has no ego at all,” Lassman says. “He’s incredibly bright and confident with the wonder and awe of a child. I think that’s part of his magic.”

Lassman and O’Rourke, who was retiring from Alcoa to focus on consulting, volunteering, and lecturing on ethics, began meeting for coffee on a monthly basis to share stories.

“Bill says we’re colleagues, but to me, he’s my mentor,” Lassman says.

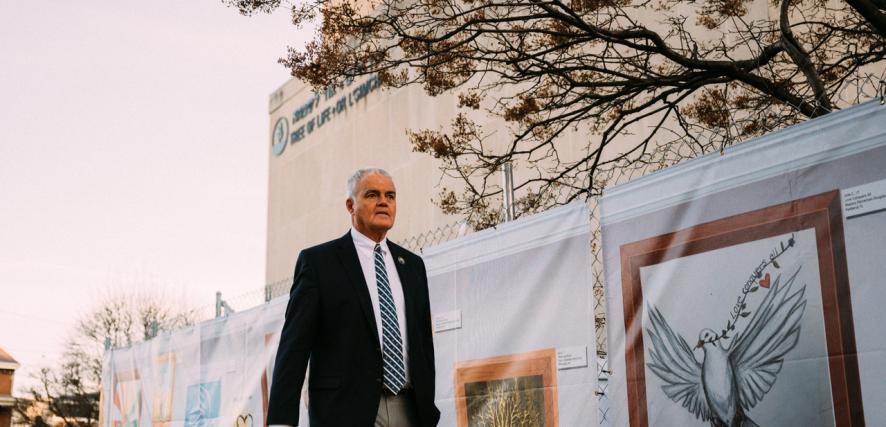

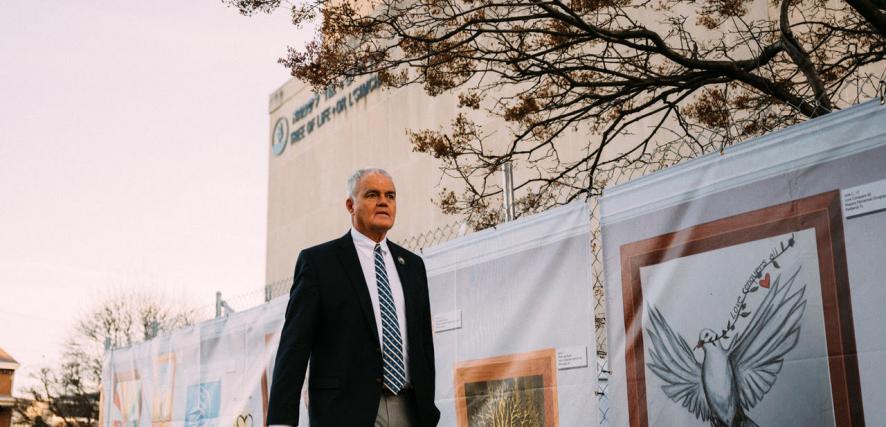

Their relationship intensified in January 2019 after O’Rourke received a call from Sam Schachner, president of the Tree of Life – Or L’Simcha Congregation. He was asking O’Rourke to consider becoming the interim executive director for the synagogue.

Three months earlier, Tree of Life, which housed three separate congregations—Tree of Life, New Light, and Dor Hadash—became global news when a gunman entered the building during Shabbat services, killing 11 congregants and wounding seven people in the deadliest attack on Jews in U.S. history. Each congregation lost members during the shooting.

Lassman knew all too well how the attack shook the Jewish community and Pittsburgh to its core. His great-grandfather founded a synagogue in Pittsburgh in 1870. He’s on the board of the Jewish Family and Community Services, a provider of social services in Greater Pittsburgh that played a huge role in the response to the Tree of Life massacre.

“I knew he was the perfect choice,” Lassman says. “I said to him, ‘you’re incredibly empathic, you’re a leader, you have legal smarts. It will be difficult. You have a community that is suffering. Their finances are in jeopardy, but you can help them move forward. You are the complete package. You can’t say no.’”

He continued, “I told the board at Tree of Life that it was an advantage that Bill isn’t Jewish. He has no politics to play. He’ll be objective in an emotionally charged situation.”

Once again, O’Rourke took the fork in the road. He accepted the challenge. The business office of the Tree of Life moved one mile down the street to Rodof Shalom, a separate Jewish synagogue that offered the congregations a place to conduct services and offices for business.